Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is often regarded as a challenge for both children and those around them. Yet, for the child with ADHD, the concept of “disorder” may not even register. Children naturally view their behavior as “normal” (if they regard their behavior at all), and much of the difficulty they face comes from the feedback they get from their environment. This raises a critical question: what is the hardest age for a child with ADHD, and why?

Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is often regarded as a challenge for both children and those around them. Yet, for the child with ADHD, the concept of “disorder” may not even register. Children naturally view their behavior as “normal” (if they regard their behavior at all), and much of the difficulty they face comes from the feedback they get from their environment. This raises a critical question: what is the hardest age for a child with ADHD, and why?

While every child’s experience varies, the most challenging period for a child with ADHD often begins when they first encounter broader social environments, such as kindergarten and early schooling. During these years, external perceptions and societal expectations come together, magnifying the challenges for the child. By understanding the interplay between the child’s behavior and the external reactions they receive from those behaviors, we can better understand the complexities of ADHD and why these early years are pivotal.

A child’s perspective: “This is just who I am.”

A child with ADHD does not perceive themselves as “different” until they are told that they are. Their behavior, whether speaking impulsively, struggling to sit still, or zoning out during tasks, feels natural to them. To a young child, there is no internal narrative of “I’m behaving wrong.” Instead, it’s the reactions of others, including their parents, teachers, and peers, that frame their actions as problematic.

This external framing begins at home, where parents may struggle to reconcile their child’s behavior with their expectations of “good” or “normal” behavior. For example, a parent might interpret a child’s inability to sit quietly at dinner as defiance or laziness rather than recognizing it as a hallmark of ADHD. These interactions can sow the seeds of misunderstanding, leading to friction that reinforces the idea that the child’s behavior is “wrong.”

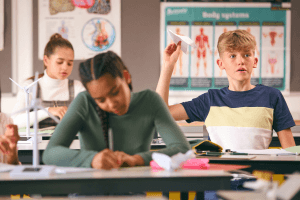

These dynamics intensify as children grow older and enter social settings outside the home. Kindergarten and early schooling introduce a new layer of expectations, such as following structured routines, adhering to classroom rules, and interacting with peers who have their own behavior patterns. For a child with ADHD, these external demands can create a perfect storm of misunderstanding and conflict.

The role of external influences in “diagnosing” ADHD

ADHD is often diagnosed when children begin to socialize more widely. This timing is no coincidence. A child’s behaviors may be viewed as quirky or challenging in the home environment, but they often lack the contrast needed for formal recognition as a disorder. Discrepancies become apparent when the child’s actions are compared to those of their peers in environments like preschool or elementary school.

For example, a child struggling to stay seated during circle time may be labeled disruptive. A teacher accustomed to a classroom of more compliant children might flag this behavior as abnormal, leading to discussions about whether the child has ADHD. Similarly, a child who interrupts frequently during group activities may be seen as rude or inattentive rather than simply exhibiting traits of hyperactivity or impulsivity.

These judgments are not made in a vacuum. They are shaped by societal expectations about how children “should” behave. Quiet compliance is often equated with good behavior while fidgeting, restlessness, or impulsivity are seen as problems to be fixed. This external framing can be deeply confusing for the child, who does not understand why their natural tendencies are being criticized.

Why early school years are tough

The transition from the home to structured environments like kindergarten and first grade marks a critical turning point for children with ADHD. Several factors make these years especially challenging:

Increased Social Exposure

Peers, too, contribute to the dynamic. Young children can be quick to label classmates as “different” or “bad,” especially if the child with ADHD struggles to follow social norms. This can lead to social isolation, teasing, or bullying, further compounding the child’s challenges.

Structured expectations

School environments often demand behaviors that are particularly difficult for children with ADHD, such as sitting still for extended periods, focusing on tasks, following multi-step instructions, and meeting deadlines. These expectations are at odds with the way many children with ADHD process information and navigate the world.

When a child struggles to meet these demands, they may face criticism or punishment, reinforcing feelings of inadequacy. Over time, this can erode their self-esteem and create a sense of alienation.

Cognitive awareness vs. emotional maturity

As children grow, they become more aware of how others perceive them. A child with ADHD may begin to notice that they are frequently reprimanded or that their peers avoid playing with them. However, their emotional maturity may lag behind this cognitive awareness, making it difficult for them to process these experiences in a healthy way. This disconnect can lead to frustration, anger, or withdrawal.

How ADHD can progress if external influences remain negative

Without recognition of the “normality” of a child with ADHD’s self-awareness, there can be a progression in their sense of difference in the years of middle school and on through the first few years after high school. In those years, children and teenagers face the widest range of structured behavior (tasks to do, deadlines to meet) and are given the least choice when it comes to avoiding tasks that they struggle with or find boring.

Shifting the focus to understanding, not fixing

Parents, educators, and caregivers must adopt a more empathetic and inclusive approach to shift this dynamic. This involves:

- Providing focused training on ADHD can help parents, caregivers, and teachers better understand the condition, and this allows them to respond to behaviors in a supportive way. For example, a teacher might learn to provide movement breaks for a restless child rather than punishing them for leaving their seat.

- Recognizing that children with ADHD may not fit traditional molds of “good” behavior is crucial. By reframing the expectations of how the child is going to behave, thereby celebrating their strengths, such as creativity, curiosity, or energy, caregivers can help the child build confidence.

- Promoting more open communication can help children navigate the social challenges of ADHD by encouraging them to express their feelings and experiences not as an admission that they somehow need to change themselves but rather as a way of telling others that it is up to them to make the adjustments in recognition of the “normality” of the person’s with ADHD’s behavior. This will validate their self-worth, and reassuring them that they are valued can also make a significant difference.

Empowering a child with ADHD

While external influences play a significant role in shaping a child’s experience of ADHD, it is also possible to empower the child to navigate these challenges. Strategies such as mindfulness exercises, structured routines, and positive reinforcement can help children develop coping skills and build resilience. These can be thought of as “survival strategies,” which are meant to smooth the passage through any episodes of unwanted behavior instead of trying to prevent them from happening by engaging in personality-changing activity, which can end up being quite confrontational.

For example, teaching a child to recognize when they feel overwhelmed and use calming techniques, such as deep breathing or a sensory break, can reduce stress. Similarly, creating a consistent routine at home and school can provide stability and predictability, which can be particularly beneficial for children with ADHD.

Conclusion

It’s necessary to rethink the whole question of what is the “hardest age” for a child with ADHD. It is not defined by the child’s internal experience but by the external reactions and expectations they encounter. Early schooling often represents a challenging period because it exposes the child to a broader array of influences, many of which may misunderstand or misinterpret their behavior.

By shifting the focus from “fixing” the child to understanding and supporting them, we can create environments that celebrate their strengths and accommodate their needs. In doing so, we empower children with ADHD to thrive, not despite their differences, but because of them.